[Thanks to Chris Schwarz’ example, each week I try to include one free post for all subscribers - this week’s is an article I wrote in 2017. Not much different since then, considering most of the content is from the 1600s…my new comments in italics]

As I study 17th-century oak furniture, I come up with many dead-ends. The surviving objects tell one part of the story, another view into this world is found in the written records of this period. The Holy Grail of 17th-century joinery would be an account book, diary or some other record of a joiner’s day and his insights into his trade. Thus far, no such record exists for early New England. What views we do get into these men’s lives and work come in short, disconnected bits found in various court records, personal diaries and other written records from the period. These snippets come back to me now and then while I’m at the bench.

I’ve been working on a carved chest with drawers recently based on some made in the Connecticut River Valley between about 1670-1700. [made two of them, this one a favorite of mine…]

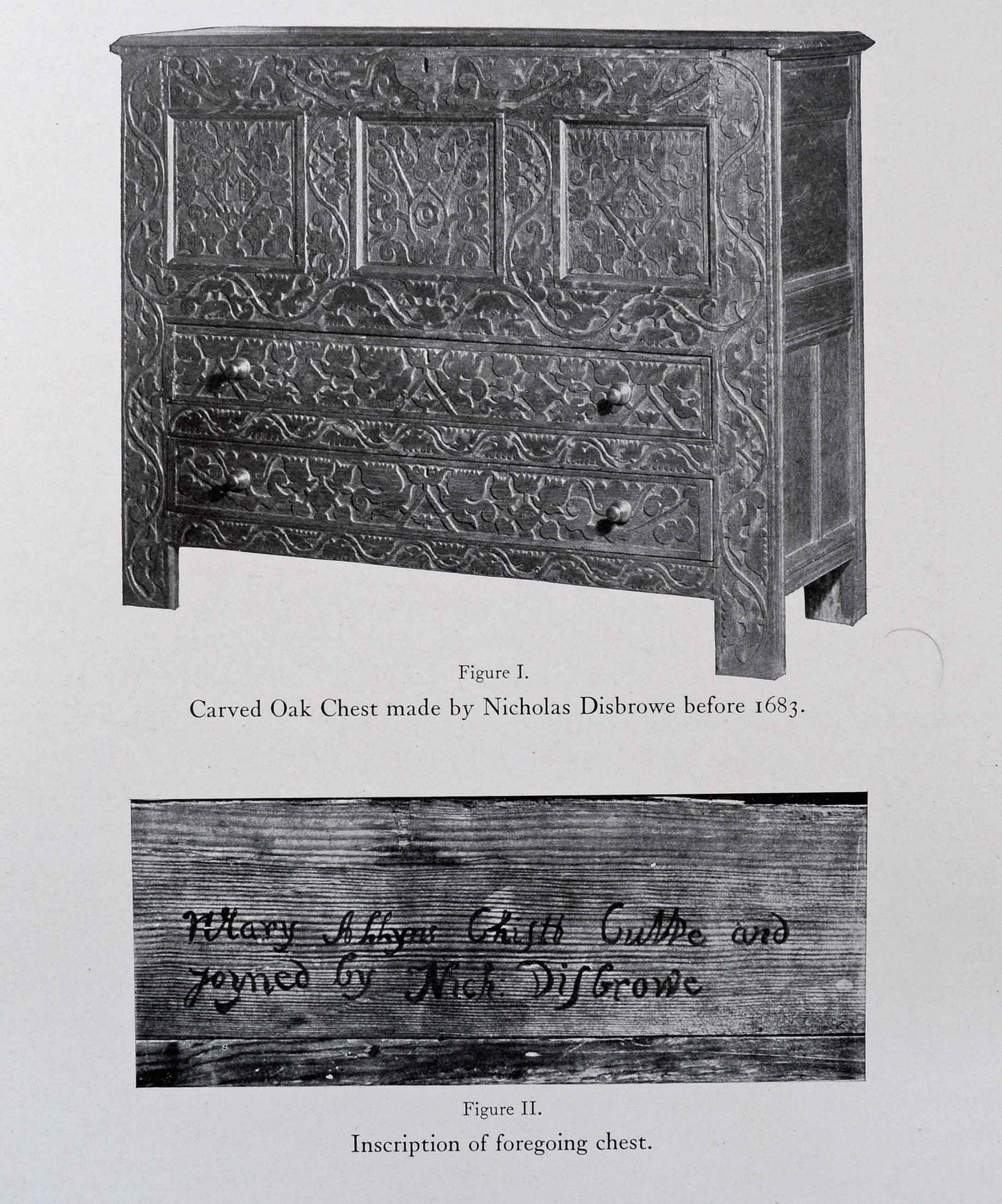

Working on this chest got me to thinking about Nicholas Disbrowe (1613-1683), a joiner in Hartford, Connecticut. He is most famous in American furniture studies for something he didn’t do - an inscription signed on a chest with drawers related to the one I’m working on now. “Mary Allens Chistt Cutte & Joyned by Nich Disbrowe” is signed on the inside of a drawer front on a chest in the Bayou Bend Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. When the inscription was first published by Luke Vincent Lockwood in the 1920s, it was accepted as “real” but has since been established as a forgery.

In the end, it doesn’t matter to me. It’s a nice chest, probably with nothing to do with Nicholas Disbrow. There are some interesting period records pertaining to Disbrow’s career though. He was born in Saffron Walden, Essex, England in 1613, the son of a joiner, also Nicholas, and grandson of William Disbrow, joiner (1554-1610). In 1628-29, the elder Nicholas was paid by the Saffron Walden churchwardens for "mending of the pulpit & a seat" and for "mending of seats & for nails"

The younger Nicholas emigrated to New England, arriving in Hartford by 1635, after serving an apprenticeship in old England. In early Hartford records, he is recorded as having built a shop 16’ square. Two things stand out about Nicholas Disbrow. His probate inventory, taken to settle his estate, itemizes his tools. From a research standpoint, this is always helpful, it gives some insight into his workshop’s capabilities.

“plane stocks and Irons, seven chissells passer [piercer} betts and gimblets £2-11-6

a parsell of small tools & two payer of compases & five handsawes £1-5-6

two fros, a payer of plyers, two reaspes a file, and a sett 10s 6d

two passer [piercer] stocks, two hammars, and fower axes 18s

two bettells and fower wedges a bill and five augers £1-4s 6d

. . . two payer of joynts & a payer of hooks and hinges

. . . joyners timber and five hundred of bord.”

The spelling is phonetic; that helps you figure it all out. The joints, hooks & hinges are iron hardware -not sure what the “joynts” are. The distinction between “joiners timber” and boards is interesting; probably referring to riven sections of oak for the joiners’ timber - like these:

The other bit has nothing to do with joinery, but just shows that life can be hard. Cotton Mather recorded that in the last year of his life, Nicholas Disbrow was “very strangely molested by stones, by pieces of earth, by cobs of Indian corn, and other such things, from an invisible hand.” An earlier charge of witchcraft against Disbrow was dismissed.

Other period records tell us something about using furniture, sometimes in ways we don’t expect. Judge Samuel Sewall of Massachusetts kept a diary, which was published in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1676, he noted that “…Mrs Brown was buried, who died on Thursday night before, about 10 o’clock. Note. I help’d carry her part of the way to the Grave. Put in a wooden Chest.”

It’s quite clear from Sewall’s writings that he knows details well, thus he knows the difference between a chest and a coffin. This diary entry made it into my files because it’s a surprising use of a chest, to me, anyway. Might not have surprised anyone at the burial.

In 1682, another unfortunate woman, “...Mrs Brattle goes out being ill; Most of the Compy goe away, thinking it a qualm or some Fit; But she grows worse, speaks not a word, and so dyes away in her chair, I holding her feet (for she had slipt down) At length out of the Kitching we carry the chair and Her in it…”

I guess, not having any personal experience moving the freshly-dead, that a chair is a good vessel for this work, because he notes it again in 1685:

“Our Neighbor Gemaliel Wait eating his Breakfast...found him Self not well and went into Pell’s his Tenant’s house, and here dyed extream suddenly about Noon, and then was carried home in a Chair, and means used to fetch him again, but in vain ...Was about 87 years old, and yet strong and hearty: had lately several new Teeth. People in the Street much Startled at this good Man’s sudden Death. Govr Hinkley sent for me to Mr Rawson’s just as they were sending a great Chair to carry him home.”

I have some chairs underway too. Something to think about.

—-

Back to 2024:

For the article, my friend Pret & I staged a photo carrying a fake-dead person - his wife Paula. We tried it in a turned chair:

And in a joined chair:

There was no noticeable difference, for us. Nor for Paula either, because she was supposed to be dead, so wouldn’t have noticed anyway. My son Daniel was off-camera and shouting to her that she needed to let her arm drop down…

Later, I heard from EMTs and firefighters that they often carry people (living) out of the house/room in chairs. Some things are timeless I guess.

OK, I have to ask how was the chest with the Disbrowe writing determined to be a forgery? I loved the photos of Pret, Paula, and you!!

Ann Bolyn was buried in an arrow chest, possibly because nobody thought to have a coffin on hand. I had idly wondered when "plyers" arrived on the scene as a distinct member of the tool group Squeezer Things. Evidently by the 17th century.