[another in a series of blog posts about furniture history and the research I learned to do when I started out studying 17th-century New England furniture. The joinery tradition from Braintree, Massachusetts was the first I studied in depth - starting in 1990-91. This post follows some previous writings, this time with the focus on local history and genealogy, including probate records. This week I’m teaching a class in making a carved box - and some of these motifs have made it into the students’ work…]

After determining that the carved chests & boxes we were studying had been made in 17th-century Braintree - the next step was to try to determine who might have made them.

It’s funny to me, going back to review this stage of my career. I was an art-school dropout, never having done any real research/writing projects beyond high-school book reports or stuff like that.. So I was learning a lot, quickly. I dug out a folder of notes from that period - yellow legal pads, hand-written. During those early days I used to write the stuff long hand, I eventually decided to take a typing class at the evening classes in the local high school. A few years later came my first computer. But most of these Braintree notes precede the typewriter & computer.

I spent a lot of time in the Braintree Historical Society or the Quincy Historical Society - (Quincy was cut out of Braintree in 1792), the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston, the Massachusetts Archives and more. I was instantly hooked on this project and became fully obsessed.

Reading the town records was a start - those were published in the 20th century - I had to go to the historical societies to read them. Now, they’re online - if you’d care to look at them go here https://archive.org/details/cu31924025963665/page/4/mode/2up

The town records start in 1640 and the 17th-century records don’t take up much space, maybe the first 100 pages reach to about 1720. I figured by then the furniture I’m studying would be out of style...and its makers dead.

Reading through the records I made lists of people I wanted to learn more about. If there was any indication that a man was a tradesman, I made a note. The next stop was the state Archives, where the early probate records are kept. This place became my favorite stop. I remember going in with a list of about a dozen names and once I learned how things worked, going up to the counter and asking to see the wills and inventories of these people. They showed me how to use the index and fill out the request slips. And then - they brought me the original documents! Handed them to me...and off I’d go back into the reading room and try to make sense of the period writing. Learning all the time at that point. They used to let me photocopy them!

After a bit of this, I found out the wills and inventories were copied into books at the time. That meant I could read the books (sorted by county) and that way I could in theory read ALL the inventories for the town of Braintree, rather than cherry-picking people one by one. I went through those county books and made notes of furniture and tools listed in Braintree inventories.

The first example in my notes is Moses Paine, died in Braintree in 1643:

One bed stoole 4sh

One chest of linnen given by will one chest £13/7

Yron tooles 10sh

One table kneading trough and wooden vessels £1

One trunk one chest one chaire and small table £1

Another - John Shepard, died 1650, had “carpenters tooles” worth £4/8/3.

The folder I dug out today has excerpts from about 70-80 inventories. Based on the records available to us, the most active families of woodworkers in the town were the Belchers and Savells. Gregory Belcher (1606-1674) and his sons Moses (1635-1691) and Samuel (1637-1680) were carpenters, as were Samuel’s son and grandson, both named Gregory. Gregory Belcher’s inventory has nothing very significant in it, nor does Samuel’s. Moses Belcher’s does:

Seven chests £1, five boxes, one trunk, £1, two chests in the parlour £2, one cubard £3, four tables, three joint stooles, £2/5, 13 chairs 16 shillings, 2 dozen cushings (cushions) £2, for Richard Russells time £8, one cradle, two cubbards 14 shillings, axes, sawes beetle & wedges £1/10, saws, augurs old iron other lumber £3

The listing for Richard Russell’s “time” means Russell was Belcher’s apprentice. I found no further records about him. Seven chests worth £1 doesn’t indicate very significant objects, but the “two chests in the parlour” at £2 does, along with the highly-valued cupboard.

But the Savell family stood out for a couple of reasons. John Savell was the only person actually called “joiner” in any 17th-century Braintree records – but that record is his death:

“John Savil Joyner died 19-9-1687” (p. 664)

The vital records don’t start until 1643, prior to that, Braintree records were filed in Boston. Among those early Braintree/Boston records is the birth of John Savell:

John the sonne of William Savell was born the 22 2 1642

So that led to William Savell. The earliest New England citation for him is from Edward Everett Hale, Jr., ed. Note Book kept by Thomas Lechford, Esq. Lawyer, in Boston, Massachusetts Bay, from June 27, 1638 to July 29, 1641, (Cambridge, MA.: 1885, reprint, Camden, ME., 1988) :

The peticon of Willm Savill of Cambridge joyner

Sheweth that wheras he did worke heretofore at Cambridge for Mr Nathaniell Eaton and for parte of this peticoners pay he received by apprizement one cowe & a steere calfe for 25 £ wch then was 5 £ overvalued at least & out of wch he payd 9£ to workmen in money besides then presently cattle fell more & so have done ever since and now they are not worth above 12£ wch another bull calfe increased having bin kept about a yeare so that yor peticoner is damnifyed 13 besides 2£ 10 for the keeping of them since wch amounts to in all to 15 £10 . In tender consideration whereof yor peticoner humbly prayeth he may be relieved in the premises according to equity against the said Mr Eaton & his estate heere by the order of this Court and that especially because the apprisement aforesaid was made not to this peticoner, but halfe a yeare before for payments to other men & he was faigne to take these though so much too deare because he apprehended not any other way to be satisfyed. So restes.

This petition is undated but seems to fall about June 1641. Eaton, the first president of the college, was dismissed from his position in September 1639, so that at least provides a date by which Savell was in Cambridge. He next appears in Braintree records when his son John was born there in 1642. He lived there until his death in 1669, married three times and had several children. As noted, the eldest son John became a joiner. His brother Benjamin Savell (1645-1722) is charged in the town records to help with carpentry work, often in conjunction with Caleb Hobart.

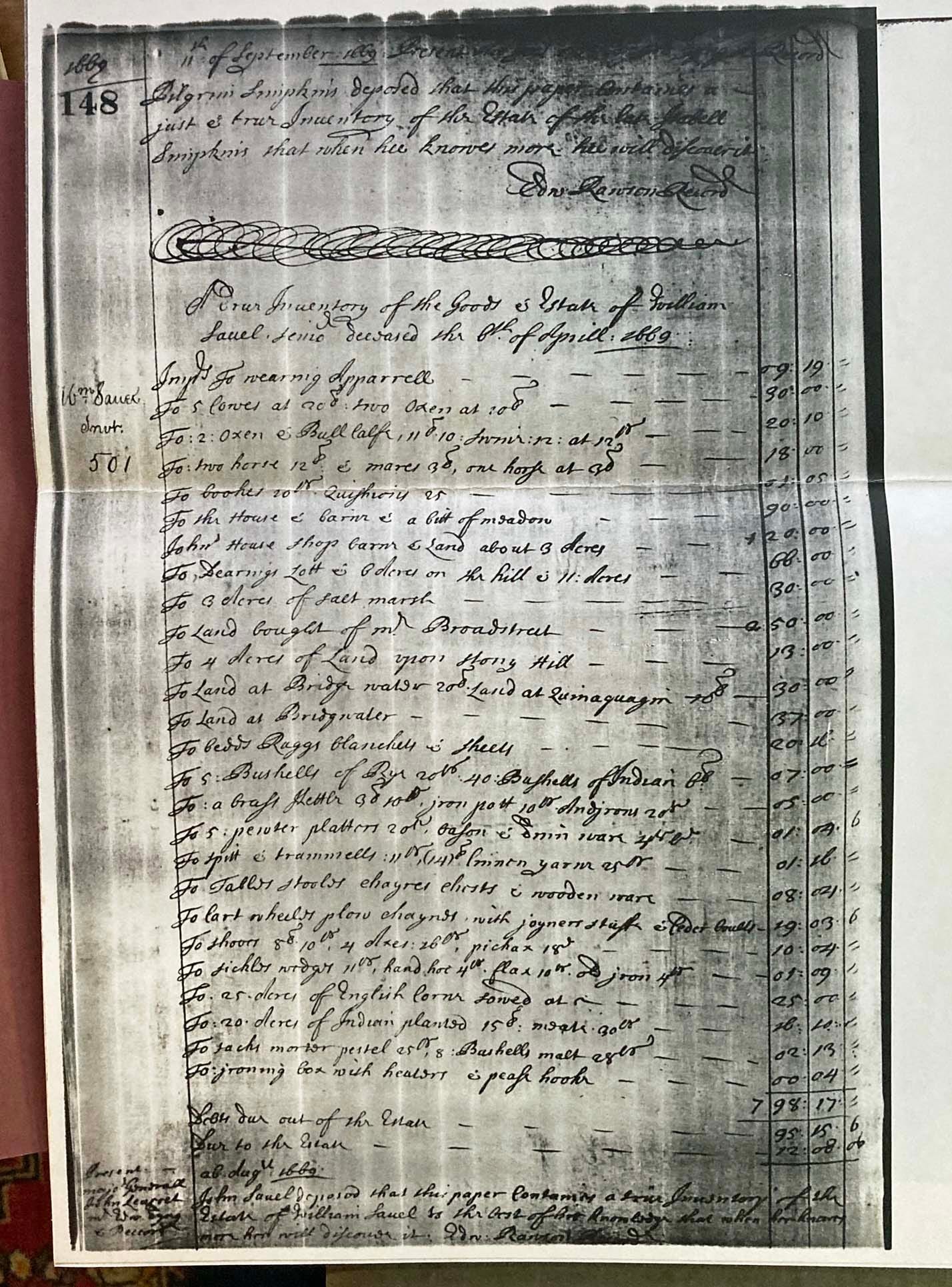

William Savell, Sr died in 1669. His will and inventory shed some light on things. If you want to pick away at the whole inventory, you’ll need to enlarge it.

The lines that interest me are these:

Johns House shop barn & Land about 3 Acres £20

Tables stools chayres chests & wooden ware £08-04

Cart wheels plow chaynes with joyners stuff & ceder boults £19-03-6

In his will, dated February 1668, William Sr. left John “the whole House & barn & shop & tooles, stuffe as Timber pertaining to his trade” and instructed that his “sonn William . . . live as an Apprentice with . . . John Savel . . . until hee bee 21.” An article of agreement attached to the will also specified that his wife, Sarah (Mullins Gannett), receive the “whole estate. . . she brought to [her husband] for her own use & to dispose of forever with a chest with drawers & a Cubbert.”

Two things in particular - we find out that William Savell the youngest son apprenticed with his older brother. And that they made chests with drawers - plural. Not chests of drawers, but a chest with drawers. Like this:

The “joiners’ stuff” is the material - riven bolts of red and/or white oak. The cedar bolts could be either more joinery stock or fence posts, clapboards or what else? Some of the chests in the group have floor boards and drawer bottoms made of riven Atlantic white cedar.

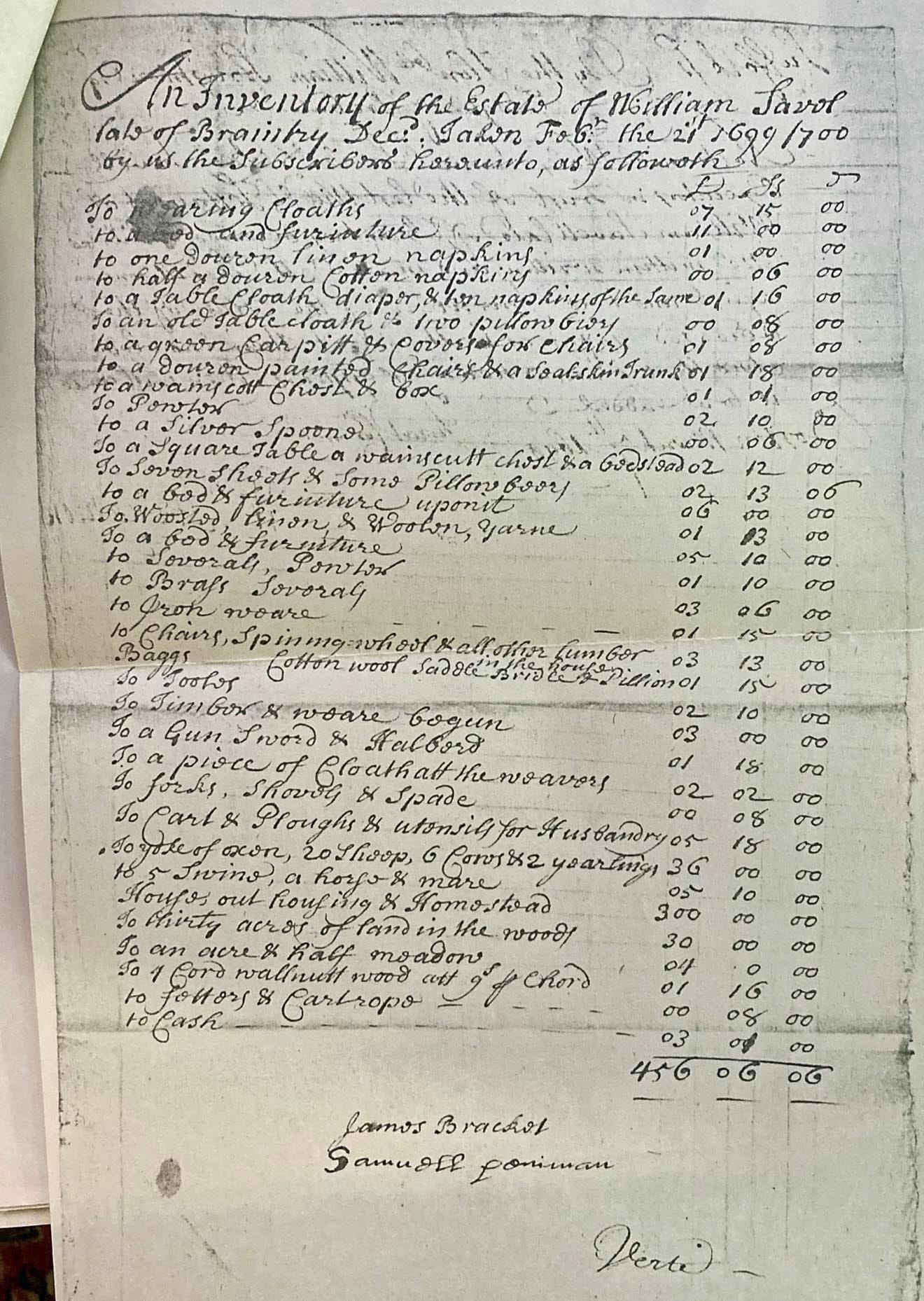

Of all the inventories I read from Braintree, only ONE uses the word “wainscot” to describe a chest - that of William Savell the younger, who died in 1699/1700. (the double date is due to England using the “old” calendar, in which the year began in March - while the rest of Europe used the “new” calendar, starting the year in January...thus Wlliam Savell died February 21st in 1699 “Old Style”/1700 “New Style.”)

You’ll have to enlarge it to read for yourselves - but there’s several informative lines:

“a dozen painted chairs & a sealskin trunk” worth £1/8; “a wainscott chest & box” valued at £1/1; and “a square table a wainscott chest & a bedstead” at £2/12. Further down the list is “tooles” at £2/10 and “Timber & weare begun” valued at £3.

Now - to tie the Savells to the furniture is easy. The chest that sold at Sotheby’s in 1988 descended from John Bass of Braintree and his wife Ruth Alden Bass. John’s parents were Samuel and Anne Bass. They came first to Boston, then to Braintree as some of the earliest inhabitants of that town. Their home in England was Saffron Walden in Essex - where their marriage record from 1625 gives us Anne’s maiden name - Savell. She was born in Saffron Walden in 1601, parents - William Savell, joiner and wife Margaret. I don’t have a definite record of her brother William’s birth - but they’re clearly brother and sister. One of the executors of William’s will was his “brother Bass.” There were further records of Savell and Samuel Bass being partners in some real estate transactions.

What we have yet to find are any pieces of English furniture that are dead-ringers for the Braintree stuff. I’ve always felt that the pieces we know are so consistent in their format and construction that there should easily be an English antecedent. Thus far, nothing has come to light. Maybe someday.

Very interesting! Thanks.

Have you seen the carved chests at the Chicago Institute of Art?

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/59450/chest

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/56095/box

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/56132/chest

Sorry if it’s irrelevant to this post but recently visited and thought I’d mention it to you if you hadn’t seen them.