I am taking an idea from Chris Schwarz to do a regular, once-a-week post free to all subscribers. I have a large backlog of old posts and writings that I’ll pull up and expand. This one falls under the heading “period records” - stuff taken from my research into 17th century woodworking.

In the 16th & 17th centuries, some craftsmen compiled lists of what they perceived as a basic set of tools for a young man starting his career in the woodworking trades. They just didn’t publish them on blogs or websites, or in books and other far-reaching media. The documents I’m thinking of are legal records; apprenticeship contracts usually filed in local courts in 16th and 17th-century England.

Tool historian W. L. Goodman published excerpts based on a number of apprenticeship contracts drawn up in England. The full contracts stipulated the terms of the apprenticeship; the duration, the responsibilities of each party, when the arrangement is to begin and end, and for our interests, often what tools the master will provide the boy upon completion of the contract. Goodman read through many records to pull out the good stuff. The earliest ones are in Latin, or a Latin/English/French hybrid:

“1555 Simon Shorting to James Richeman:

. . . vnum le Joyntor vnum le fore plane vnurn le hammer vnum le hande saw vnum le hatchet vnum le parsour vnum le mortas wymble vnum le framin chesell & vnum duodecima les karving tooles . . .”

This excerpted record tells us that Simon Shorting agreed to provide his apprentice James Richeman with a set of joiner’s tools at the end of his term. The tools are: one jointer, one fore plane, one hammer, one hand saw, one hatchet, one piercer (brace & bit) one mortise wimble, one framing chisel, one dozen carving tools. Perhaps the “mortise wimble” is an auger for boring out large mortises before using the framing chisel; or it’s a mistake and should read “mortise chisel.” “Wimble” is usually a term for a boring tool, often a brace. But we know this craftsman calls his brace a piercer. If only these men knew how much we would hang on their every word!

In Bristol, 1594, John Sparke agreed to outfit Humphrey Bryne with the following:

“. . . a Rule a compass a hatchet a hansawe a fore plane a joynter a smothen plane two moulden planes a groven plane a paren chysell a mortisse chesell a wymble a Rabbet plane and six graven Tooles and a Strykinge plane”

What more could a person need? Some sharpening stones or more saws perhaps? I wonder about life with just one saw. Either your saw is too coarse for cutting shoulders of tenons, or too fine to break down rough stock. The seven planes will cover most any need a joiner would have then, the grooving plane being used to plow grooves for frame-and-panel work. Perhaps you’ve seen what Matt Bickford can do with just two molding planes, so while in this case the sky is not the limit, a lot of things were possible. The “wymble” is a brace and bit; it goes by various names; wimble, brace, borer, bitstock and piercer among them. The “graven” tools are carving gouges, so-called for engraving. The stryking/striking plane is familiar to readers of Joseph Moxon’s book Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handyworks, where he describes its use in shooting joints.

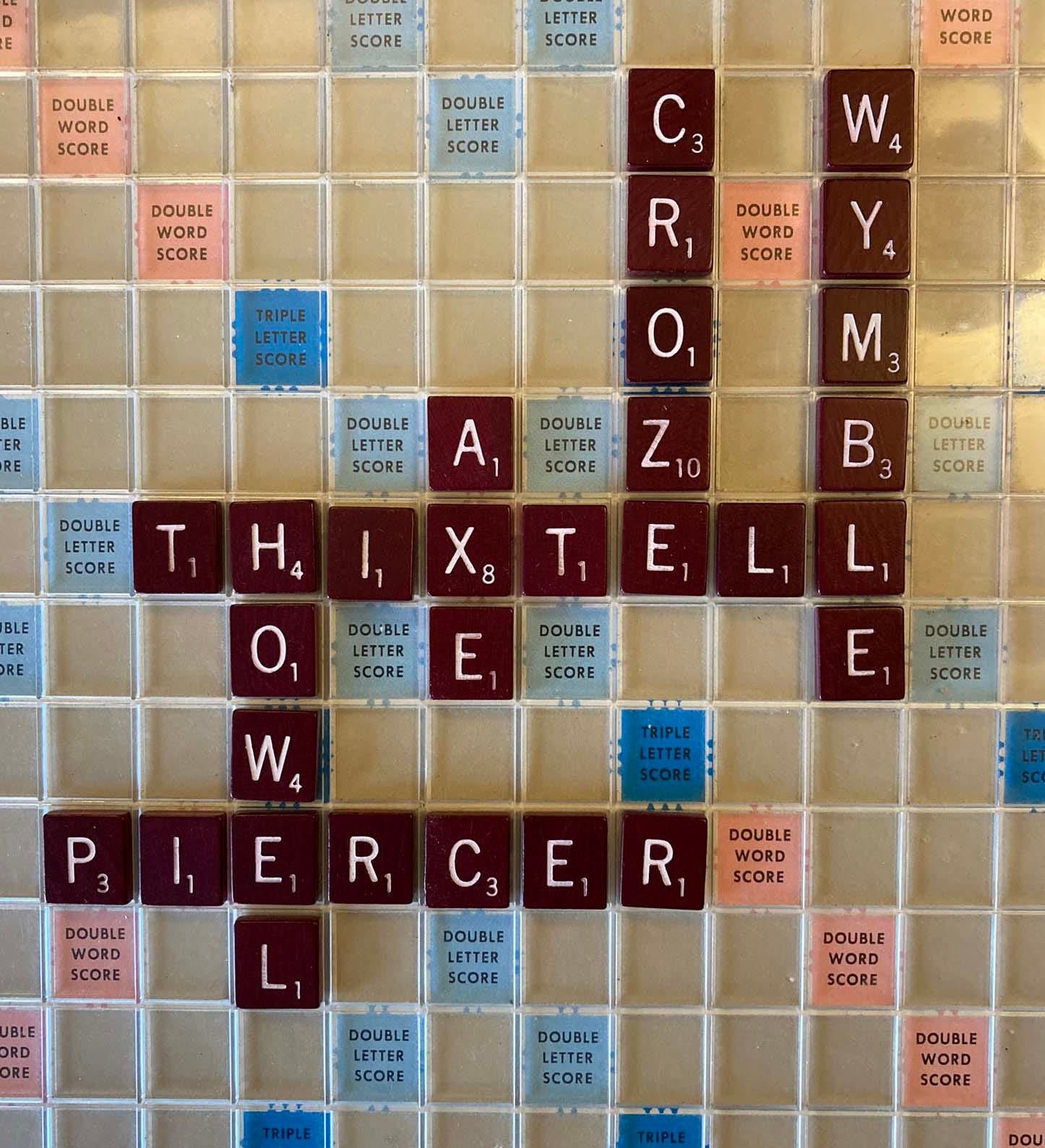

There are many trades represented in these records. Among the other woodworkers are carpenters, shipwrights and coopers. The cooper’s tools read like a Scrabble game run amok. Try this on for size

1561 James Hemson to Robert Joyner, Cooper:

. . a barge axe a Thixtell a Howel a Crowes a passer a payer of compas & a headyng knyfe . . .

Thixtell, howell, crowes - what on earth are these things? The thixtell, thixell - like any period term it can show up in a variety of spellings, is an adze. It cuts a bevel around the inside of a barrel in which the cooper cuts the croze, a groove that accepts the heads of the barrel. The tool that cuts the croze is called a croze. It’s like a giant marking gauge with sawteeth for cutting the groove, instead of a pin to scribe a line.

The howell is more confusing. I looked in Salaman’s Dictionary of Woodworking Tools (1975) and he calls a howell a plane that performs a similar task to that assigned to the thixtell above. It cuts a bevel around the inside of the barrel, to prep it for the croze. He also says it’s a term used in the US. But the early records clearly indicate that a cooper needs both a thixtell and a howell. That tells me that the one or the other of these names had a different meaning in earlier records. Or the howell cleans up after the thixtell. Thixtell is absent from Salaman’s Dictionary, so that word must have fallen out of use by then. Howell is present in 17th-century New England sometimes. A 1680 inventory for John Harris, cooper includes:

a bung boarer and two shaveing knives 10s a crissiff 7s a Round shave 6d an Ax 8s two Adses 12s A heading knife and Howell 4s6d three compasses 6s two Crowsing Irons 3s two breast Wimble Stocks and a head Pullee 3s Chalk 1s4d Truss hoops

and other hoopes 5s (a comb knife and Steel 1s3d)

1000 of Staves £1-10

Speaking of New England - in the records there I did sometimes find apprenticeship contracts. They’re not common - I’ve often wondered why. But there’s no telling. A particularly detailed apprenticeship indenture from Plymouth Colony dated 1653 describes the obligations of both the master and apprentice:

Thomas Savory senior of Plymouth and Ann his wife Doe…covenant with Thomas Lettice of Plymouth aforesaid Carpenter; That their sonn Thomas Savory Juni aged five years or thereabouts…shall Remayne and continue with the said Thomas Lettice untill hee bee of the age of one and twenty years; …after the manner of an apprentice; the said Thomas Lettice is to find unto his said apprentice…meat Drinke apparrell washing and lodgin and all other necessaries fitt for one in his Degree and calling and to teach an Instruct his said apprentice in the arte or trade of an house carpenter in as able a mannor as himselfe is able to prforme it, likewise…the said Thomas Savory is to Doe and prforme unto his said master all faithfull service and not to neglect his said masters business not absent himselfe from the same by night or Day without Lycence from his said Master; hee shall not marry or contracte himselfe in marriage…he shall not Imbezell purloyne or steale any of his goods or Reveale any of such seacrets that ought to bee kept…Thomas Lettice covenanteth…that the said Thomas Savory shalbee by him or his appointment and att his charge Taught to Read and write the English Tongue…Lastly when the term of time abovementioned is by the said Thomas Savory the younger fully attained; that then the said Thomas Lettice or Ann his wife (in case shee bee the longer liver) shall provide for and Deliver unto theire said apprentice two suites of apparell vizt one for best and another for working Daies and also…certaine Carpenters tooles…one broad axe two playnes two Augers and a sett of Chissels; & an hand saw…

(“Extracts from the Deed Books of the Plymouth Colony” quoted in Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture 1630-1730, (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1988) pp. 57-8.)

Coopers, carpenters, joiners, shipwrights - all these craftsmen, all these tools. These records are just snippets of course. Who among us has kept to our first kit of tools, with no additions? I imagine earlier tradesmen would amass larger tool kits if and when their work took off. Think about Moxon telling his readers to visit the ironmongers in Foster Lane, London for steel handsaws. Can’t you see it now? Moxon drops that name, and prices go through the roof...

The Goodman article that brought this stuff to my attention is W. L. Goodman, “Woodworking Apprentices and their Tools in Bristol, Norwich, Great Yarmouth, and Southampton, 1535-1650” Industrial Archaeology 9, no. 4, (November 1972) 376-411. Another version is W. L. Goodman, “Some Elizabethan Woodworkers and their Tools”, Furniture History, vol. 7 (1971), pp. 87-93.

"Imagine Scrabble w 17th century spelling"...the first Dictionary in English spelled alphabetical "Alphabeticall"…anythyng gose!

c'est vrai