[a follow-up to the previous post about pitsawing. This one is documentary records from 17th century America - mostly from the New Haven Colony. Years ago I spent a lot of time reading various colony records and copying out what I found about tradesmen and their work.]

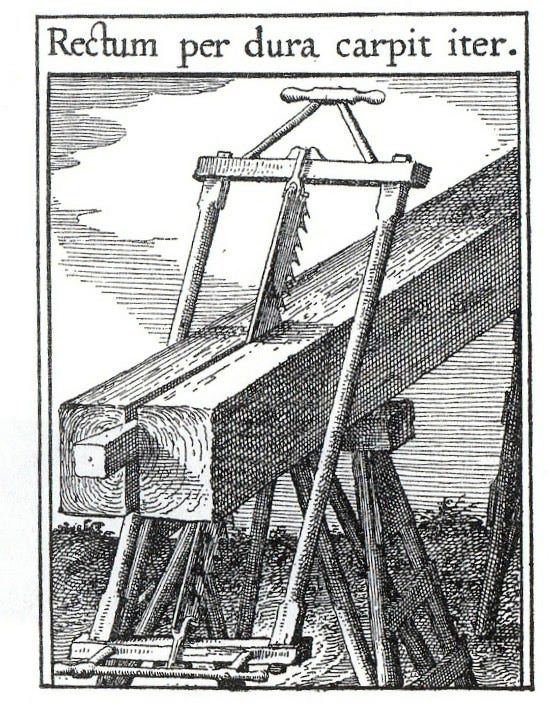

[not an English saw, the framed version was continental. This engraving is Dutch, 1614.]

Most of the pitsawn evidence I know of from 17th century New England is in buildings and that’s not stuff I have many photos of...I used to rubberneck when my friends were studying houses, but I was never completely up to speed with that aspect of research. Much harder to study a house than a chest.

But there’s other evidence about pitsawing - the written records of the period. First place I’ll turn my attention to is the records of the New Haven Colony - where there were very detailed records, later compiled into a book: Charles J. Hoadly, editor, Records of the Colony and Plantation of New Haven, from 1638 to 1649 (Hartford: Case, Tiffany and Company, 1857). First, we’ll sort the wages and daily hours for different tradesmen, from June 1640

In callings wch require skill and strength, as carpenters, joyners, plasterers, bricklayers, shipcarpenters, coopers and the like, mar [master] workemen not to take above 2s6d a day in sumr, in wch men may worke 12 howers, butt lesse than 10 howers dilligently improved in worke cannot be accounted nor may be admitted for a full dayes worke, nor in winter above 2s a day, in wch at least 8 howers to be dilligently improved in worke. And by advice of approved mr workemen the names of others who in severall trades are to be allowed for mr workemen are to be sett downe. Butt all workemen in the former and like trades, who are not as yet allowed to passe under the names of mar workemen, not to take above 2s a day in sumr and 20d a day in winter as above expressed.

No sawyers there. But there were certainly sawyers working in the town.

Sawing by the hundred not above 4s6d for boards. 5s for plancks. 5s6d for slittworke and to be payd for no more than they cutt full and true measure. If by the dayes worke, the top man or he that guides the worke and phaps findes the tooles, not above 2s6d a day in somr, and the pitt ma, and he whose skill and charge is lesse, not above 2s, and a proportionable in winter as before. If they be equall in skill and charge, then to agree or divide the 4s6d between them.

Right off the bat, I have questions. “Sawing by the hundred”? Is that 100 feet? 100 boards? Boards seems wrong, without some clarification as to what constitutes a “board.” So I’m guessing it’s 100 feet. Now, is it linear feet or board feet?

It’s 4 1/2 shillings for boards, 5 shillings for planks - which are thicker than boards. Same number of kerfs to produce them, just more timber in them. Then comes “slit work” - at an even higher price, 5 1/2 shillings. My memory is that slit work is thin stuff. We’ll come back to it.

Nice that they’re to be paid for what they cut, “full and true measure.” Now, if they’re paid by the day’s work - the top sawyer gets 2 1/2 shillings a day, bottom sawyer just 2 shillings. Those are summer wages, winter a bit less. If there’s no hierarchy between them, they get to split the 4s 6d. So I guess they’re sawing a hundred of boards per day. In summer...

Sounds like they (well, not the sawyers I’d bet) squared the log before sawing boards - (my italics)

Hewing and squaring timber of severall sizes, one wth another, butt the least 15 inches square, well done that a karfe or planke of 2 inches thicke being taken off on 2 sides, the rest may be square for boards or for other use, not above 18d a tun girt measure. And for timber sleightly hewn a price proportionable, or by days wages. As for sills, beames, plates or such like timber, square hewen to build wth, not above a peny a foote running measure.

Now comes pricing for sawn boards and planks.

Inch boards to be sould in the woods nott above 5s9d p[er] hundred.

Halfe inch boards in the woods not above 5-2 p hundred

2 inch planke in the woods not above 7-0 p hundredinch boards in the towne not above 7-9 p hundred

halfe inch boards in the towne, not above 6-2 p hundred

2 inch planke in the towne not above 11-0 p hundredSawen timber 6 inches broad and 3 inches thicke

In the woods running measure not above} ¾ fard p foote

In the towne not above 1d p foote

Sawne timber 8 inches square running measure in the woods not above }1d ¼ p foote

In the towne not above 2d p foote[all these quotes above from 1640, pp. 36-38]

Is the slit work now being called “halfe inch boards”? They’re worth less than the inch boards, so maybe not slitwork - which in the first quote are priced higher than inch boards.

And let’s get straight how long is winter - and keep an eye on your neighbor, you might earn some cash for ratting them out.

It is ordered that not above 4 months shall be accounted for winter in workmens wages, provided thatt they improve 8 howers dilligently in worke every day when they expect to be payd a dayes worke…

…that if any workmen take more than is appoynted for worke and wages, he thatt gives itt and he thatt takes itt shall each of them pay a dayes worke fine, and the informer shall have the 4th part. [p. 44]

In 1641 the town records re-establish rates - which have dropped a bit for sawing.

Worke taken by the greate, sawing by the hundred to be payd for no more then is cutt full & true measure, boards nott above 3s 8d, planks 4s, slit worke 4s 6d.

When men saw by the day, the top man or he whose skill guides the worke, and phaps findes the tooles, in somr, and winter respectively as mar (master) workmen, and the pitt man as unskillfull or nott approved mar workmen, and if they be equall in skill and charg, then to devide the wages, wch shall be 22d a pecce in somer and 18d in winter.

Leaving the New Haven records, a bit earlier is this reference to saw pits. Writing about an early settlement in Newfoundland, John Guy in 1610 noted:

“…we have digged a saw-pitt hard by the sea side, and put a timber house over it [co]vered with pine boardes; there are two paire of Sawyers workinge in it, the pyne trees make good and large bordes and is gentle to saw, they be better than the deale bordes of norway, there is now a pine tree at the saw-pitt, that is about tenne feete about at the butt, and thirtie feete longe is eight feete about…” (pp. 61-2)

“…If an expert man to make pitch and tarr were sent hether a double commoditie would arise because by that meanes the woodes would be ridd the sooner, when a saw-mill is erected here we may serve the fishinge fleete wth boords to make fishinge boats…”

[Gillian T. Cell, English Attempts at Colonization, 1610-1630 (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1982) pp. 63-4.]

There’s more of this sort of thing throughout early New England records, but this is enough to get a bit of the picture. In 17th century New England the workmen converted logs into useable material a number of ways - pitsawing being just one method. Millsawing, splitting/riving and hewing were employed whenever one method made more sense than another.