more period records; the turner's company of London

[I’ve made this post available for all subscribers - a sampling of some of the research into 17th century records I’ve done over the years. More shop work coming soon. PF]

I’m nearing the end of my cupboard project and one thing that means is the shop is pretty crowded. Thus not much room for photography - and most of my blog posts revolve around photos I shoot as I work. But I’ve been looking back over some old posts and piles of research I did in years past and was thinking about London trade companies (today we often refer to them as “guilds”) and apprenticeships, etc. So I opened my notes from reading The Worshipful Company of Turners of London - Its Origin and History by A.C. Stanley-Stone, (London: Lindley-Jones & Brother, 1925)

“ ...no person using the misterie (the craft) was to be allowed to be a master workman, or set up a shop for such work, until he had satisfied the Master, Wardens, and Assistants that he had served seven years as apprentice and two years as a journeyman, and had also made such pieces of work as might be comanded.”

I take this to mean that a turner working within the city limits had to show his “indentures” - papers proving he’d served his time, additionally, at times he might be directed to make what the company elsewhere refers to as a “proof piece.” Here’s two examples of these situations:

“11th November 1614 Lawrence Clarke was fined £3 for setting up his shop without having served two years as a journeyman and was directed to make for his proof piece a linen wheel and bring it to the Hall. On the same day, Thomas Fawken...was ordered to make for his proof piece a man’s arm stool.”

What an “arm stool” is I don’t know. Today we don’t think of stools as having backs, let alone arms. But backstool is a common term in 17th century England and New England. This might be the only time I’ve seen the term arm stool.

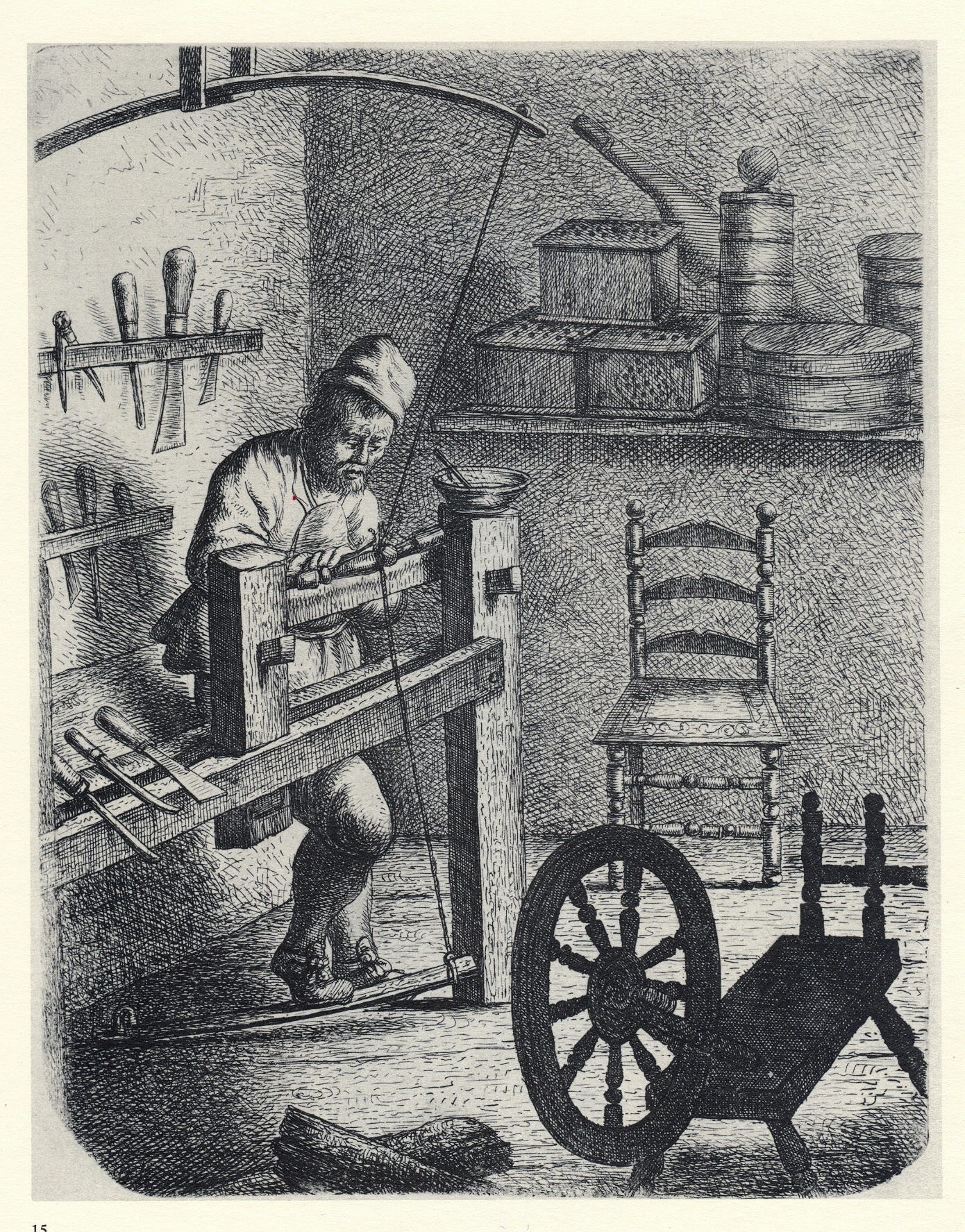

[1635 Jan van Vliet depiction of a turner]

Back to Stanley-Stone’s book:

“There was a certain amount of fear that some of the proof pieces produced by applicants for membership might have been made by someone other than the applicant, and to meet this, on the 20th May 1617 it was ordered that there should be a lathe, a cutting block, and a winding block set up in the warehouse to make the proof pieces by such as were appointed to make them. The lathe had not yet been set up on the 13th July 1617 when Richard Chamberlain was ordered to make...a high stool for a child.”

I’m glad for these histories of the trade companies - but it’s important to keep in mind that the author(s) are at times quoting the period records, at other times summarizing them. There’s one I’ve used many times - this record about the Company seizing chairs -

“20th February 1615 It was directed that the makers of chairs about the City, who were strangers and foreigners, were to bring them to the Hall to be searched according to the ordinances. When they were thus brought and searched, they were to be bought by the Master and Wardens at a price fixed by them, which was 6s per dozen for plain matted chairs and 7s per dozen for turned matted chairs. The effect of such an order...all chairs which came into London had to be submitted to the Company and if approved, were taken over at the fixed price. The Turners reaped the benefit by the removal of possible competition.”

Several things here - the “strangers & foreigners” - some of these might in fact be foreigners from other countries, but strangers are probably just British workmen who are not from the city, thus not members of the Company. They bring their chairs to the city, thinking to sell them, but the Company seizes them & pays for them at prices determined by the Company!

Then there’s the whole “plain matted chairs” versus “turned matted chairs” issue. I have taken this to mean some of these chairs are shaved rather than turned. Matted chairs have fiber seats, often rushes.

A common problem was turners working for joiners or carpenters. One fear was that the joiners or carpenters were learning to turn their own work. And it seems the Company would look the other way if a fine was paid:

.

“12th November 1622 William Gryme was charged for putting his apprentice to work at the trade of Turning within a joiners to make Turner’s work for the joiner, and was ordered to take him home ... 6th July 1630...Christopher Bere was charged with working in a joiner’s house and teaching them the trade of Turning.”

“...it was ordered that every Turner who worked and turned in the shop or other rooms of any Joiner, Carpenter, or Coachmaker should pay ten shillings for every week he should continue so working after being warned.”

When I first learned about the London Companies, or trade guilds, I thought they were nice succinct packages - turners here, joiners there, that sort of thing. But one catch is that a tradesman only needs to be a member of a London Company - it doesn’t have to be the one aligned with his trade.

“7th March 1625...complaint of the Master and Wardens of the Company of Turners against Richard Newberrie and others free of the Company of Salters, but using the trade of a Turner, for making, as they alleged, “insufficient bandeleeres” and for refusing to bring their wares to the...Turners Hall...”

Another of Stanley-Stone’s summaries is worth looking at:

“18th February 1629...a Petition...that the Company of Turners “is verie smale,” and consisted altogether of “handy trades men”; that within the last five years about thirty householders free of other Companies had earned a living by turnery, and were not under government as regards their trade, but took as many apprentices as they liked to the great harm of the Company of Turners...”

That can really throw a monkey wrench in research. If you want to know about joiners in London at that time - you’d think if you learn all about the Joiners Company, you’d be covered. But somehow you have to cast your net wider. The most detailed example of this sort of thing is the book Early Planemakers of London: Recent Discoveries in the Tallow Chandlers and the Joiners Companies by Don & Anne Wing (the Mechanick’s Workbench, Marion, Massachusetts, 2005) The Wings got through this problem backwards - they found an “early” plane marked with the name John Gilgrest - and by searching his name found him listed in the Tallow Chandlers Company - the whole story (as of 2005) is outlined in their excellent book.

-----------

About papers and indentures. From time to time you come across records concerning artisans having their “papers” - their contract/indentures proving the terms of their apprenticeships. Or not having them. One court case in 1660s Salem Massachusetts concerns a father taking his son back after he’d been apprenticed to a blacksmith. The father lost the case, the boy was to be returned to his master. My notes in brackets:

Salem, June 1662: Thomas Chandler v Job Tyler, for taking away his apprentice Hope Tyler, and detaining him out of his service. Verdict for the plaintiff, the boy to be restored to his master.

Search warrant, dated June 23, 1662, issued by Daniel Denison, to the constables of Ipswich and Wenham, for the apprehension of “Hope Tiler a youth of about 13 yeares of age, who is run away from his M[aste]r Thomas Chandler of Andover who as I am informed is entertained by Richard Coy” and to bring him to the court at Salem if sitting, or before said Denison to be proceeded with according to law.

Thomas Chandler’s bill of charges, 3£7s.

Nathan Parker, aged about forty years, testified that about four years since, Job Tiler and Thomas Chandler desired deponent to make a writing to bind Hope Tiler, son of Job, apprentice to Thomas Chandler, which he did according to his best skill. This writing, Mr. Bradstreet afterward saw and perused and adjudged it to be good and firm. The term of years mentioned was nine years and a half and said Chandler was to teach him the trade of a blacksmith, to read the Bible and to write so far as to be able to keep a book so as to serve his turn or to keep a book for his trade, and to allow him meat, drink, washing, lodging and clothes. Deponent was to keep said writing safely, which he did for about three years, and Job Tiler often asked deponent to let him have it, but he refused, because it was agreed by both parties that deponent should keep it.

Finally Moses Tiler came with John Godfrey to deponent’s house, as his maid servant and children told him, when deponent, his wife and his maid were not in the house, and sent the elder of the children out of doors. As the younger child told deponent when he returned, they took the writing down, which he had stuck up between the joists and the boards of the chamber, and the child thought they burned it in the fire. And when deponent returned, he feared the writing was lost, because he certainly knew it to have been there when he went out of the house about an hour or two before, as he had taken it from his pocket when he came from Mr. Bradstreete’s. He had also warned his children not to meddle with it, which he verily believed they could not, for he himself was forced to stand up in a chair to raise up the board to put it under. The elder boy before he was sent out of doors by said Moses, saw said Tiler and Godfrey look up to the place where the writing stuck and he told them that they must not meddle with the writing for their father had charged them not to do so. Deponent had never seen the writing since, and asking said Tiler and Godfrey for it, they did not deny that they had taken it down, but said they did not have it and did not know where it was, etc. Sworn, June 16, 1662, before Daniel Denison.

Georg Abbott, aged about fifty years, deposed. Sworn in court.

Wiliam Balard, aged about forty‑five years, deposed that about six weeks since, the house of Job Tyler being burned, he gave said Tyler’s wife leave to come with her family for a time and live at his house. Her husband at that time was not at home. She accordingly did so and there remained to this date.

John Godfre deposed that he saw Moses Tyler, Goodwife Tyler being there also, take down the indenture in Nathan Parker’s house. Deponent went with them to their farm, and Moses said to him, “Godfre I have got my Brothers indentures and nowe lat Chandler dou what he can wee will take away hope frome him and that night I see the induentuer by moses burned in the sight of his father and then he said now father you may take away hop when you will from Chandler and lat him prove a righting if he can and thay gratly Tryemped.” Sworn in court.

[Godfrey, I have got my brother’s indentures and now let Chandler do what he can, we will take away Hope from him and that night I see the indenture by Moses burned in the sight of his father and then he said now, Father, you may take away Hope when you will from Chandler and let him prove a writing if he can and they greatly triumphed.]

George Francis Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Court Essex County, Massachusetts, 8 volumes, (Salem, Massachusetts: Essex Institute, 1911-21) 2:403-404