In an earlier post I wrote about riving and planing oak for my joined furniture. https://peterfollansbeejoinerswork.substack.com/p/working-riven-radial-oak-boards

Most of this work is concentrated on the radial, or ray, plane. I often joke about how I make my living on the ray plane - a chest like the one above shows the growth ring, or tangential, plane on the edges of the four “stiles” (corner posts.) - other than the drawer pulls, everything you see there is the radial plane.

First - what are medullary rays? I’m not a wood scientist, so I only know a short answer. They are cells that provide nutrients across the tree’s width - from the pith (the center of the log) toward the sapwood and bark. Some wood, like ash, the rays are not visible with the naked eye. Others, like oak or American sycamore, you can’t miss ‘em.

We’ll focus on oak. The rays are visible in several views. On the end grain they are silvery lines radiating out from the center. On the radial plane they can take several shapes, depending on how close to the actual ray “plane” the board is cut. Wide blocky patches, small sinuous wavy lines and everything inbetween. For thirty-five-plus years I’ve been looking at rays in oaks - smaller in red oak, larger in white oak.

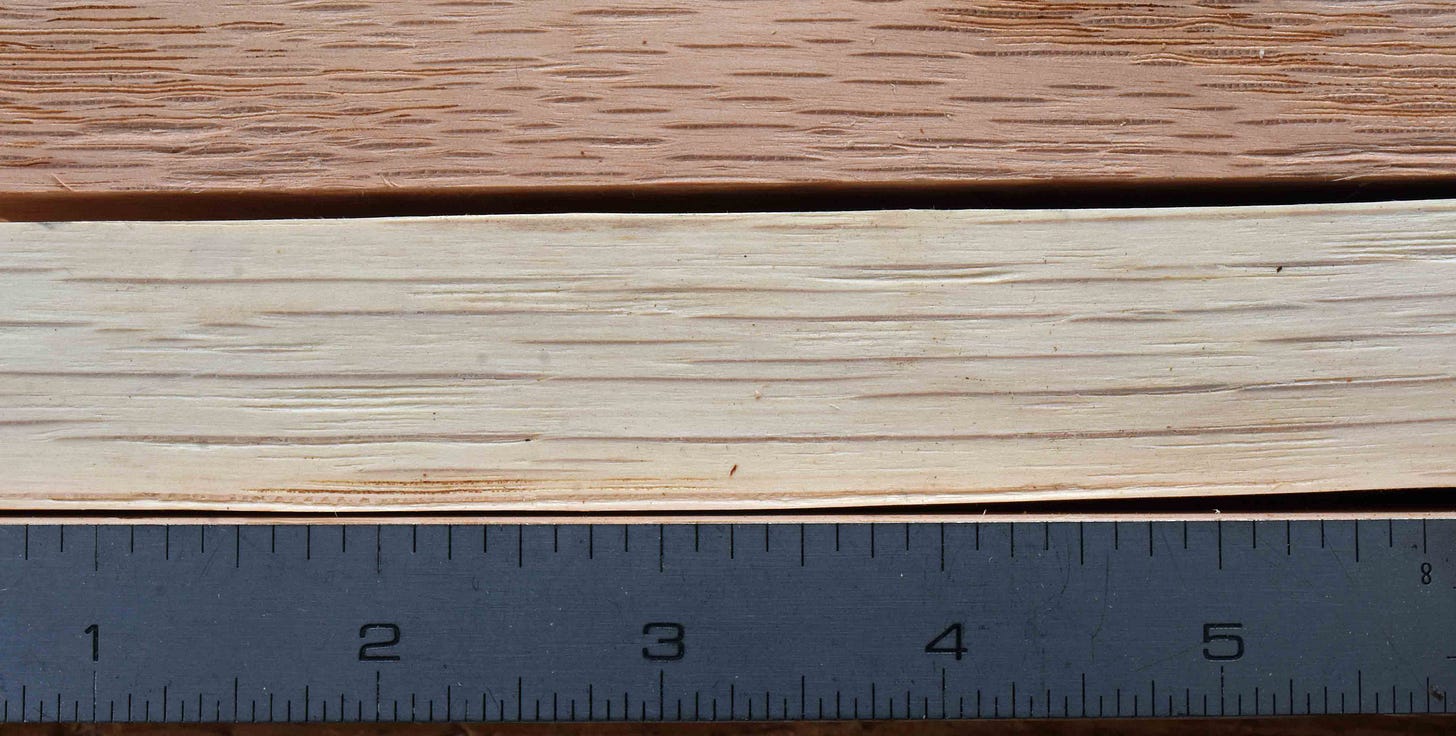

That’s the general rule. But looking on the ray plane can be misleading - if the board is cut a bit “off” the ray plane, the figure/shape of the rays can vary. Last fall, I met Craig Brodersen, a professor of Plant Physiological Ecology at Yale University. And he showed me to look at the tangential surface to see the length of the ray - longer in white oak, shorter in red.

What you’re seeing there is the thickness of the ray’s cells - if I’m understanding that correctly. But why did it take me so long to look at the rays on this plane? One of those things that once somebody shows you, you think “of course...”

Here’s a detail of the end of a chest I made about 15 years ago - showing the rays on the end panels. Only the end faces of the stiles show the growth-ring/tangential plane. The shapes/sizes of the ray figure showing on those panels is determined by the log - how straight it grew, was there twist in it? Yes, always. Some more, some less.

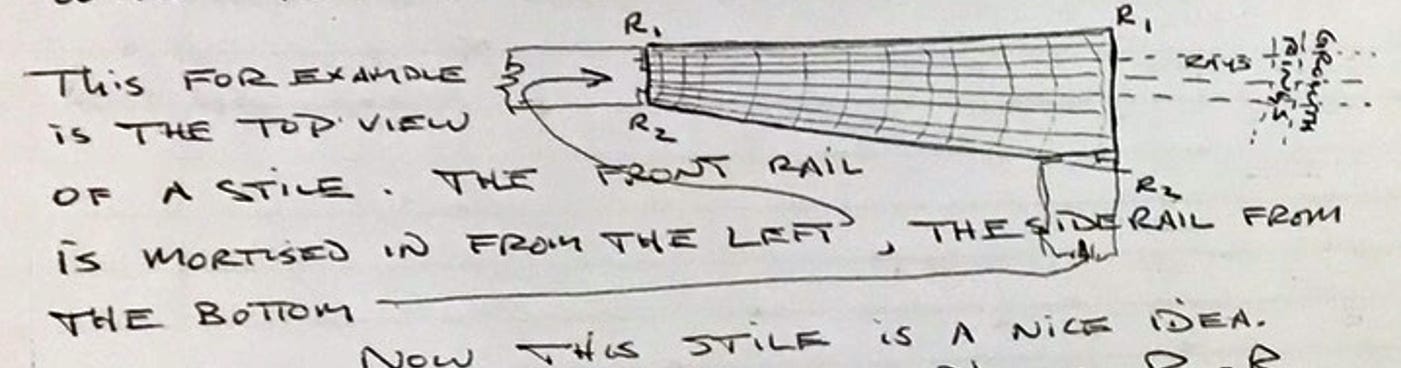

The theory I learned from Jennie Alexander was just that - a theory. Many times she diagrammed the front stile’s cross-section - with its inner and outer faces perfectly aligned on the radial planes.

But trees don’t grow perfectly. Here’s a photo from a chest made in Connecticut, late 17th century - neither the inner nor outer face of the stile is perfectly aligned on the rays -

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Follansbee's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.